The deer lay in a small open space close to a clump of acacias, and we had advanced to within several yards of our kill when we both halted suddenly and simultaneously. Whitely looked at me, and I looked at Whitely, and then we both looked back in the direction of the deer. "Blimey!' he said. "Wot is hit, sir?"You might be wondering why this series is named Dinosauria Caspakensis, given the first two entries into its records are not dinosaurs at all. I use the term quite deliberately: the Dinosauria was, in the first place, a loose grouping of three creatures. Owens had little notion of the sheer variety of forms prevalent in this great dynasty of beings in 1842, and indeed, the latest taxonomic tumult suggests in its most extreme form that an entire family of what we used to call dinosaurs weren't members of the Dinosauria at all!

"It looks to me, Whitely, like an error," I said; "some assistant god who had been creating elephants must have been temporarily transferred to the lizard-department."

"Hi wouldn't s'y that, sir," said Whitely; "it sounds blasphemous."

"It is more blasphemous than that thing which is swiping our meat," I replied, for whatever the thing was, it had leaped upon our deer and was devouring it in great mouthfuls which it swallowed without mastication.

- Chapter 5

There's also the fact that it isn't clear the "dinosaurs" of Caspak are dinosaurs as we understand them at all: likewise for the pterosaurs, plesiosaurs, prehistoric mammals, and even (especially) the humans. If we go by our current understanding of evolutionary biology, many creatures on Caspak must, logically, all be members of the same species, undergoing metamorphic upheaval that makes the life cycles of insects & amphibians positively stagnant in comparison. Nonetheless, for the sake of simplicity, and to evoke the style of the time - to pick the most dynamic and thrilling name - I decided to stick with Dinosauria over the more prosaic Fauna or Animalia, which would probably be more technically correct.

In fact, only three members of the Dinosauria are actually named in The Land That Time Forgot. The first of these was encountered by Tyler and Whitely while out hunting for some venison: I figured that since Olson was immortalised by the crew of U-33, and Tyler already has an eponymous taxon, that the very strange creature they encountered should be named Allosaurus whitelyi ("Whitely's Different Lizard").

Discovery of the Allosaurus

|

| Where it all began. |

Compared to Pterodactylus and Plesiosaurus, Allosaurus is practically a latecomer to the field of Mesozoic palaeontology - though it has something of a convoluted history. The first bones which can be reliably attributed to Allosaurus were brought to the scientific community by famed geological surveyor and former Union Army physician Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden in 1869: locals at Middle Park in Colorado found curious objects which they described as "petrified horse hoofs." Hayden passed one such specimen on to Joseph Leidy.

Leidy is probably most famous as the "conscientious objector" in the infamous Bone Wars between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope: he protested at the two bone-hunter's destructive adventures, and feared that they would ruin not just the reputation of American palaeontology, but precious scientific discoveries in the process. At this point, however, the Bone Wars were yet to commence, and American palaeontology was still a young and relatively innocent field. At first, Leidy thought that the fossil - a partial tail vertebra - was a new species of the still little-understood European theropod Poikilopleuron, which he named Poicolopleuron valens ("strong varied ribs"; consistent spelling was not a priority in the Gilded Age of Palaeontology). However, after further study, Leidy reconsidered, and after placing the creature in Megalosaurus ("great lizard"), he concluded that the creature was not just a new species, but a new genus. In 1870, Leidy gave the creature the name by which it would be known for decades - Antrodemus valens ("strong chamber-bodied").

For several years, this tiny fragment was all the scientific community knew of what would become one of the most recognised dinosaurs of them all. In 1877, Othniel Charles Marsh collected a number of fragments - part of the right humerus, a rib, a tooth, a toe bone, and three vertebrae fragments - from Garden Park, also in Colorado, and described the remains as a new species: Allosaurus fragilis ("fragile different lizard"). Over the course of the Bone Wars, Marsh and his rival Cope would describe several new species which were remarkably similar to Leidy's Antrodemus and Marsh's Allosaurus: just a year later, Marsh described Creosaurus atrox ("cruel creation lizard") and followed with Labrosaurus ferox ("wild fierce lizard") the year after - both considered synonyms of Allosaurus fragilis - while Cope described Epanterias amplexus ("embracing buttressed vertebrae"), now argued to be Allosaurus amplexus.

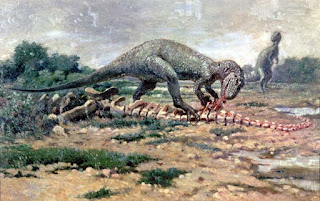

The first reasonably complete Allosaurus was discovered in Como Bluff in 1879, but because Cope never unpacked the specimen, it wasn't formally described until 1903. Thus, Marsh beat his rival to the punch with the first nearly complete Allosaurus to be described with a specimen found in Garden Park in 1883. That first skeleton was later mounted in 1908, and became the inspiration for one of Charles R. Knight's most enduring paintings - cementing the popular image of Allosaurus for generations.

Following the Bone Wars, palaeontologists struggled to navigate the wreck and ruin left in the two foes' wake - such as the hastily-written, insufficiently detailed descriptions - with palaeontologists like Samuel Wendell Williston suggesting that many fossils belonged to the same species. It wasn't until 1920 that the first attempt to make sense of these old bones took place - one being rather controversial. Charles W. Gilmore concluded that not only were several specimens actually Allosaurus, but that Allosaurus itself was indistinguishable from Antrodemus. As anyone who knows the story of Brontosaurus would remember, the older name takes priority, and so the creature known throughout the world as Allosaurus was given the junior synonym treatment in favour of the now-accepted Antrodemus...

A COMPOSITE skeleton of a carnivorous dinosaur, whose well-preserved bones were excavated two decades ago by University geologists from a quarry in central Utah, was exhibited for the first time last month, February 18th, in Guyot Hall. An Antrodemus (Allosaurus) specimen which roamed the earth during the Jurassic Perior some 140 million years back, the new arrival is a strapping adult measuring some 25 feet in length and 12 feet in height.

- Princeston Alumni Weekly, Volume 61, 1960

The giant herbivorous dinosaurs certainly had enemies, in the form of the large carnivorous dinosaurs, the carnosaurs exemplified by such genera as Allosaurus (more properly Antrodemus) and Ceratosaurus.

- The Age of Reptiles, Edwin Harris Colbert (1965)

Among them is another well-known carnivorous dinosaur, Antrodemus [Allosaurus], which was larger and more muscular than Ceratosaurus.

- Fossil Amphibians and Reptiles, W.E. Swinton (1965)

... at least until 1976, where the decision was overturned on the basis of the specimen's fragmentary nature and lack of detail about its locality. Nowadays, Antrodemus is considered a nomen dubium, while Allosaurus gets to be in Walking With Dinosaurs and Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom. Hence how you'll find Antrodemus on postcards, reference books, dinosaur parks, town streets, and metal album covers, as well as Allosaurus.

The Allosaurus in Literature

Lord John never hesitated, but, running towards it with a quick, light step, he dashed the flaming wood into the brute's face. For one moment I had a vision of a horrible mask like a giant toad's, of a warty, leprous skin, and of a loose mouth all beslobbered with fresh blood. The next, there was a crash in the underwood and our dreadful visitor was gone...

- Arthur Conan Doyle, The Lost World Chapter XI - "For Once I Was The Hero" (1912)

From about the year 1920 to the 1980s, Allosaurus occupied the same curious neverland as Brontosaurus: it was a name rejected or at least qualified by the scientific community at large, yet which crops up again and again in fiction, pop science, and elsewhere throughout the world. It's a heartwarming irony that both have ultimately been vindicated as distinct creatures from Antrodemus and Apatosaurus without jettisoning the other genera.

Allosaurus may have appeared in The Lost World... or it may not. The theropod which menaced the expedition was never conclusively identified by Challenger or Summerlee - it is simply one of the possible identities the two scientists propose - but Doyle's description influenced depictions of Allosaurus in dozens of adventures:

"The indications would be consistent with the presence of a saber-toothed tiger, such as are still found among the breccia of our caverns; but the creature actually seen was undoubtedly of a larger and more reptilian character. Personally, I should pronounce for Allosaurus."

"Or Megalosaurus," said Summerlee.

"Exactly. Any one of the larger carnivorous dinosaurs would meet the case. Among them are to be found all the most terrible types of animal life that have ever cursed the earth or blessed a museum."

- Arthur Conan Doyle, The Lost World Chapter XI - "For Once I Was The Hero" (1912)Malone encounters the Allosaurus/Megalosaurus later:

I stood like a man paralyzed, still staring at the ground which I had traversed. Then suddenly I saw it. There was movement among the bushes at the far end of the clearing which I had just traversed. A great dark shadow disengaged itself and hopped out into the clear moonlight. I say "hopped" advisedly, for the beast moved like a kangaroo, springing along in an erect position upon its powerful hind legs, while its front ones were held bent in front of it. It was of enormous size and power, like an erect elephant, but its movements, in spite of its bulk, were exceedingly alert. For a moment, as I saw its shape, I hoped that it was an iguanodon, which I knew to be harmless, but, ignorant as I was, I soon saw that this was a very different creature. Instead of the gentle, deer-shaped head of the great three-toed leaf-eater, this beast had a broad, squat, toad-like face like that which had alarmed us in our camp. His ferocious cry and the horrible energy of his pursuit both assured me that this was surely one of the great flesh-eating dinosaurs, the most terrible beasts which have ever walked this earth. As the huge brute loped along it dropped forward upon its fore-paws and brought its nose to the ground every twenty yards or so. It was smelling out my trail. Sometimes, for an instant, it was at fault. Then it would catch it up again and come bounding swiftly along the path I had taken.

- Arthur Conan Doyle, The Lost World, Chapter XII - "It Was Dreadful In The Forest" (1912)This "lizard-kangaroo" Allosaurus is possibly inspired by another creature - to contextualise properly, we must go back to the Bone Wars. In 1866, Cope described an amazing find - an articulated, reasonably complete skeleton of a large carnivorous dinosaur, one of the very first in the Americas to be discovered. Cope named this creature Laelaps aquilunguis ("storm wind with claws like an eagle's"), the generic name borrowed from a great hunting-dog of Greek mythology gifted by Zeus to Europa.

Cope believed that Laelaps was an active, energetic creature, and theorised that the creature leapt onto prey, using its powerful hind-limbs and tail to kick like a kangaroo:

The lightness and hollowness of the bones of the Laelaps arrest the attention of one accustomed to the spongy, solid structure in the reptiles. This is especially true of the long bones of the hind limbs; those of the fore limbs have a considerably less medullary cavity. The length of the femur and tibia render it altogether probably that it was plantigrade, walking on the entire sole of the foot like the bear. They must also have been very much flexed under ordinary circumstances, since the indications derivable from two humeri, or arm bones, are, that the fore limbs were not more than one-third the length of the posterior pair. This relation, conjoined with the massive tail, points to a semi-erect position like that of the Kangaroos, while the lightness and strength of the great femur and tibia are altogether appropriate to great powers of leaping...

... We can, then, with some basis of probability imagine our monster carrying his eighteen feet of length on a leap, at least thirty feet through the air, with hind feet ready to strike his prey with fatal grasp, and his enormous weight to press it to the earth. Crocodiles and Gavials must have found their bony plates and ivory no safe defence, while the Hadrosaurus himself, if not too thick skinned, as in the Rhinoceros and his allies, furnished him with food, till some Dinosaurian jackalls dragged the refuse off to their swampy dens.

- Edward Drinker Cope, "The Fossil Reptiles of New Jersey," The American Naturalist (1868)

Unfortunately, as was often the case in the early days of palaeontology, the name Laelaps was preoccupied - in this case, by a genera of mites. Upon discovering this, Cope's rival Marsh did what any gentleman would do - nabbed the dinosaur and renamed it for himself. Laelaps aquilunguis became Dryptosaurus aquilunguis ("tearing lizard with claws like an eagle's"). (At least he granted Cope the consolation of retaining the species name). Nonetheless, the poetic and romantic name Laelaps persisted for some time, and it was under this name that Charles R. Knight produced one of the most celebrated pieces of palaeoart ever painted:

This image has been homaged and referenced in Dinosaur art, media and museum mounts for decades, for the foresight in depicting dinosaurs as vigorous and mobile creatures, and for the sheer dynamism of the action.

Allosaurus whitelyi

Burroughs' description of Caprona's Allosaurus is quite detailed compared to some of the other creatures:

The creature appeared to be a great lizard at least ten feet high, with a huge, powerful tail as long as its torso, mighty hind legs and short forelegs. When it had advanced from the wood, it hopped much after the fashion of a kangaroo, using its hind feet and tail to propel it, and when it stood erect, it sat upon its tail. Its head was long and thick, with a blunt muzzle, and the opening of the jaws ran back to a point behind the eyes, and the jaws were armed with long sharp teeth. The scaly body was covered with black and yellow spots about a foot in diameter and irregular in contour. These spots were outlined in red with edgings about an inch wide. The underside of the chest, body and tail were a greenish white.

Ten feet seems well within the historical and palaeontological height range for Allosaurus, whether it's a smaller variety standing straight in a "tripod" stance, or a larger variety in a more horizontal posture, as depicted in Knight's illustrations & the famous American Museum of Natural History mount. As Cope suggested Allosaurus was plantigrade, that would have knocked a few feet off its height.

The A. whitelyi Tyler and Whitely encountered could thus be a subadult like "Big Al," a rough estimate of its non-erect stance, or the visual measurement of 10ft simply being an absolute minimum estimate.

The "hopping" motion as suggested by Cope and interpreted by Conan Doyle strengthens the "leaping Allosaurus" meme which dominated depictions of the creature for decades. Unlike its Maple White Land counterpart, however, A. whitelyi's head is "long and thick," rather than the "broad, squat, toad-like face" of The Lost World: this is more in line with palaeontological discoveries. Burroughs accurately describes the mouth stretching back past the eye, which is also reflected in the fossil record, albeit without the prodigious cheek muscles that broke up the serpentine comparisons.

A. whitelyi's colouration is a spectacular divergence from the usual slate grey or mossy green given to dinosaurs, especially in early 20th Century fiction & paleoart. Black and yellow spots with red outlines & greenish white underline: that sounds more like a venomous snake, tropical skink, or rare lizard. Why is A. whitelyi so flamboyantly coloured? There are plenty of natural explanations: it could be signalling that it is poisonous, or venomous, or both - or mimicking a species that is. Alternatively, it could be camouflage, recreating the dappled sunlight piercing the jungle canopy. It could even be advertising - not something you'd normally expect in ambush predators, but Caspak is a strange land, after all.

We were about a quarter of a mile from the rest of our party, and in full sight of them as they lay in the tall grass watching us. That they saw all that had happened was evidenced by the fact that they now rose and ran toward us, and at their head leaped Nobs. The creature in our rear was gaining on us rapidly when Nobs flew past me like a meteor and rushed straight for the frightful reptile. I tried to recall him, but he would pay no attention to me, and as I couldn't see him sacrificed, I, too, stopped and faced the monster. The creature appeared to be more impressed with Nobs than by us and our firearms, for it stopped as the Airedale dashed at it growling, and struck at him viciously with its powerful jaws.

Nobs, though, was lightning by comparison with the slow thinking beast and dodged his opponent's thrust with ease. Then he raced to the rear of the tremendous thing and seized it by the tail. There Nobs made the error of his life. Within that mottled organ were the muscles of a Titan, the force of a dozen mighty catapults, and the owner of the tail was fully aware of the possibilities which it contained. With a single flip of the tip it sent poor Nobs sailing through the air a hundred feet above the ground, straight back into the clump of acacias from which the beast had leaped upon our kill - and then the grotesque thing sank lifeless to the ground.That A. whitelyi could keep up with the creature for such a distance proves it is not the slow, lumbering monster of later dinofiction. The strength of A. whitelyi's tail is clearly developed for locomotion as well as defence, much like the modern kangaroo: it's possible that the tail could function as a third leg, too, which would aid it in acceleration and efficiency.

The reptilian resilience of P. olsoni and P. tyleri is once again reflected in A. whitelyi, as like those creatures, it takes a long time for it to realise it's dead:

Olson and von Schoenvorts came up a minute later with their men; then we all cautiously approached the still form upon the ground. The creature was quite dead, and an examination resulted in disclosing the fact that Whitely's bullet had pierced its heart, and mine had severed the spinal cord.

"But why didn't it die instantly?" I exclaimed.

"Because," said von Schoenvorts in his disagreeable way, "the beast is so large, and its nervous organization of so low a caliber, that it took all this time for the intelligence of death to reach and be impressed upon the minute brain. The thing was dead when your bullets struck it; but it did not know it for several seconds - possibly a minute. If I am not mistaken, it is an Allosaurus of the Upper Jurassic, remains of which have been found in Central Wyoming, in the suburbs of New York."This theory of dinosaur nervous systems being so inefficient that it takes several seconds, possibly even a minute, for the signals to reach the brain has been discounted. This reached its ludicrous limit in the case of sauropods, where it was genuinely believed by some that the distance between brain and tail in the larger species was so great that a theropod - like Allosaurus - could start feasting on a Brontosaurus without it even feeling the bite for a good minute or two. (We'll discuss this weird trope in a future instalment).

From about the year 1920 to the 1980s, Allosaurus occupied the same curious neverland as Brontosaurus: it was a name rejected by the scientific community at large, yet which crops up again and again in fiction, pop science, and elsewhere throughout the world. It's a heartwarming irony that both have ultimately been vindicated as distinct creatures from Antrodemus and Apatosaurus. Much of Allosaurus' longevity can, no doubt, be attributed to the success of such stories as The Lost World & The Land That Time Forgot, and the plethora of works following in their footsteps.

The "leaping Allosaurus" of the two titans of early dinofiction turned up everywhere. Allosaurus features quite heavily in F.V.W. Mason's "Phalanxes of Atlans" (1931), where they are used as war-dogs for the Hollow Earth civilisation of the title - usually to leap onto enemy war-Diplodocus. The curious "Dinosaurs vs Aliens" subgenre also depicted Allosaurus using its mighty bounds to repulse Martian invaders intent on colonising pre-human Earth in Philip Barshofsky's "One Prehistoric Night" (1934), complete with a cover openly paying homage to Knight's Laelaps (seen above). Carl Jacobi's "The World in a Box" (1937) depicts a more science-fiction oriented tale - again, with kangaroo-Allosauruses. Even alien Allosauruses of Venus "leaped" onto Venusian Diplodocuses in Frank J. Bridge's "The War Lord of Venus" (1930). Allosaurus was called "the leaping lizard" all the way up to the 1960s, as seen in a series of collectible cards:

Antrodemus also has a special place in dinosaur literature: it merits a mention in H.C.F. Morant's Whirlaway: A Story of the Ages (1937), and it is one of the creatures listed in the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual II, along with some other once-popular-now-obscure creatures like Dinichthys, Monoclonius, Palaeoscincus, Podokesaurus, and Teratosaurus.

Allosaurus' cinematic debut was the same as its avian cousin Pteranodon's: 1925's The Lost World. There, Allosaurus is depicted attacking a Trachodon in place of Iguanodon (and a herd of Triceratops for good measure), and of course the human expedition in a scene very faithful to the original story:

Unlike the tale, Allosaurus also takes on an Agathaumus in a particularly gory battle which goes very badly for it: during the fight, we can see Allosaurus leaping onto Agathaumas' back, just as Cope suggested, and hinted in the books. Another Allosaurus does battle with a Brontosaurus shortly after - the very beast which terrorised London at the film's conclusion.

Although Allosaurus was superceded by Tyrannosaurus in O'Brien's masterpiece King Kong, Big Al received a starring role in The Beast of Hollow Mountain (1956) - well, the last 15 minutes, at least - and his protégé Ray Harryhausen provided some of the best Allosauruses ever to rule the silver screen. The interesting motif of depicting a smaller, possibly juvenile Allosaurus is most famous in One Million Years B.C. (1966), when one such creature attacks Loana's tribe.

|

| Harryhausen's sketch doesn't look a million years off A. whitelyi, does it? |

In Harryhausen's final dinosaur adventure, a fully-grown Allosaurus takes the title role in The Valley of Gwangi (1969). Gwangi is possibly the definitive cinematic Allosaurus in the same way the Skull Island Tyrannosaurus was before Jurassic Park's Rexy changed dinosaur cinema forever: to this day, he remains an monument to Harryhausen's genius, as well as an icon for American palaeofiction: the juxtaposition of creatures the world forgot with the rough and crude adventuring that was the Wild West epitomising not just the fiction, but the reality of Gilded Age Palaeontology.

In every Harryhausen film, the dinosaurs are active, energetic, and fast-moving, just as described by Conan Doyle and Burroughs, and as vindicated by current palaeontological investigations. However, the "cold-blooded monsters" meme started to dominate scientific thought in the mid-20th Century, and fiction followed the contemporary science. Frank Belknap Long's "Temporary Warp" (1937) features a sluggish brute of an Allosaurus in this bizarre space-time-twisting adventure.

This was painfully evident in the first cinematic adaptation of A. whitelyi, Amicus' The Land That Time Forgot (1974):

From a technical point of view, it's hard to fault Roger Dicken's puppets: given the cost and time constraints, not to mention the technology of the 1970s, he and the effects team do as good a job as can be expected. However, this was just on the cusp of the Dinosaur Renaissance: the prevailing idea, in the public eye (about 10 years behind the scientific community) was that dinosaurs were sluggish, lethargic, stupid creatures that became extinct through sheer ineptitude. The idea that they were fast, bounding, warm-blooded animals was unfashionable: in a cruel irony, you might even argue that this was an attempt to "update" Burroughs to be more "accurate."

The problem is that not only that new discoveries would these new "accurate" dinosaurs being nothing of the sort only a few years later, but even by upping the ante by adding a second Allosaurus to threaten the crew of U-33, Roger Dicken's puppets are so unbearably slow it becomes almost painful to watch them. Rather than fleeing for their lives in a desperate chase, Tyler and company manage to leave the Allosaurus far behind with a brisk walk. This, even though the film decides to bump them up to T.rex size, and rather than two bullets, it takes a whole fusillade by half a dozen men to knock them down (mostly because they just stand there like big numpties rather than chase them down like their literary counterpart):

Given the clear debt Dicken's creatures owe to Knight, Burian, and other palaeoartists of yesteryear, it's unfortunate that they also lack the distinctive red-ringed black and yellow spots of the story: instead, they're a dull grey-green. There's at least one other A. whitelyi in the film, as it's also seen in the very sad and depressing producer-mandated Everything Explodes Everyone Dies climax:

The accompanying comic adaptation of the film, naturally, bore more in common with its cinematic counterpart than the literary version. It retains the "kangaroo stance," though we don't see any bounding, and while it's difficult to tell in black-and-white, there's no evidence of the distinctive colouration Burroughs described:

Curiously, the 2010 adaptation opts not to use an Allosaurus at all: in its place is some sort of gigantic quadrupedal lizard-reptile-demon-thing:

No, I don't get it either.

The 2016 Caspak comic might not be a straight adaptation, but they try their best to find a compromise between Burrough's colourful kangaroo-lizard and current palaeontological thinking:

Tan with dark stripes isn't red-ringed black & yellow spots with a green-white ventral pattern, but at least it isn't a tinted grey.

Allosaurus continues to be a popular dinosaur, and fictional individuals abound in comics, books, and films: Cutter and Hermes in Xenozoic Tales; the unnamed mother Allosaurus in Age of Reptiles; Big Alice in Land of the Lost, and beyond. It featured in countless video games, comics, films, tv series, documentaries, cartoons, and other media, holding its own against its charismatic tyrant relative. For all its outlandish colours and kangaroo-hops, A. whitleyi was one of the first - and most influential - of that fictional pride of Lions of the Jurassic.

No comments:

Post a Comment